はじめに

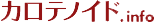

ルテイン(lutein)は、ラテン語で黄色を意味する"luteus"から派生した言葉で[1]、ケール、チリメンキャベツ、ホウレンソウなどの緑色野菜にとりわけ豊富に存在しています(図1)。

| 図1. | 主要な野菜・果物の可食部100 gあたりルテイン含有量(単位:μg) |  |

|

|

|||

ルテインと同じキサントフィルであるゼアキサンチンの濃緑色葉菜における含有量は概して低いことを考慮すれば(0〜3%程度)[4]、アブラナ科の植物であるケール(学名:Brassica oleracea L. var. acephala、英名:kale)が野菜・果物のなかでルテインの最も豊富な供給源の一つとなりそうです(図2)。

| 図2. | ケールの葉 |  |

また、動物性の食品では鶏卵が生物学的利用率の高いルテイン供給源であることが、最近のヒトを対象に行われた介入試験の結果からも明らかにされています[5,6]。

ルテインは卵黄やマリゴールドの花弁(図3)にみられるように本来黄色から橙色を呈する色素ですが、緑色野菜の場合そうでないのは、表面をおおっているクロロフィル(葉緑素)にルテインをはじめとするカロテノイドが共存しているためです。

| 図3. | マリゴールドの花(左)と その花弁(右) |

|

それ故、クロロフィル濃度とカロテノイド濃度の既知の関係から、野菜・果物の緑色が濃いほどクロロフィルのみならずカロテノイドの含有濃度も高くなると考えられています[7]。

中南米で栽培されたキク科タゲテス属のマリゴールドの乾燥花弁が米国へ輸出され、その抽出物は様々な形で動物飼料に添加されて、ニワトリの卵黄や家禽類の皮膚の黄色を強化するために30年以上も利用されてきました。このマリゴールドの黄色い色素を構成するカロテノイドの大部分がルテインで占められていることから、1995年にThe Catholic University of America(1997年〜現在:メリーランド大学に在籍)のフレデリック・カチック博士は、有機化学の分野でけん化したマリゴールド(Tagetes erecta)の抽出物(オレオレジン)からルテインを単離・精製・再結晶化するのに有効な方法を発明し、世界で初めて植物抽出物から得る精製ルテインの特許を取得しました[8]。

この画期的な発明のおかげで、僅か十余年の間にとりわけ栄養補助食品と機能性食品の応用分野で、マリゴールド由来のルテインの利用が米国市場を発端に飛躍的な伸びを見せました。

日本の健康食品業界でも、ルテインをはじめとするカロテノイドを補給目的とした商品の設計に、このようなルテイン製品やそれを含む混合物(マルチカロテノイド製剤)が選択肢の一つとなり、他の抗酸化栄養素同様、重要な成分として位置付けられるまでに至っています。

体内分布

ヒトの血液と主要組織におけるカロテノイドの分布:

ルテインは私たちの体内で合成されないため、日常的にカロテノイドが豊富に含まれる食品から適切な摂取を心掛けることが大切です。食事に由来するルテインを含む複数のカロテノイドの存在が私たちの血液や母乳中に認められます。現在までのところ25種類の食事性のカロテノイドと8種類のカロテノイド代謝物(それらのシス異性体は除く)がKhachikらにより発見されています[9-11]。

さらに、ルテインは野菜・果物を豊富に摂取している健常人の血清中に占める割合が最も高いカロテノイドの一つであることも明らかにされています(表1)。

- 表1.

- 野菜・果物を豊富に摂取している健常人の血清中の主要なカロテノイドの分布

| No. | 食事性カロテノイド | 血清中の分布(%) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | ルテイン* | 20 |

| 2 | リコピン* | 20 |

| 3 | β-カロテン* | 10 |

| 4 | α-カロテン* | 6 |

| 5 | ゼアキサンチン* | 3 |

| 6 | ζ-カロテン | 10 |

| 7 | フィトフルエン | 8 |

| 8 | β-クリプトキサンチン | 8 |

| 9 | α-クリプトキサンチン | 4 |

| 10 | フィトエン | 4 |

| 11 | アンハイドロルテイン | 3 |

| 12 | γ-カロテン | 2 |

| 13 | ニューロスポレン | 2 |

- *発表時点(1997年)の商業的入手可能性を優先

- [文献9より引用改変]

それでは、血液あるいは母乳から取り込まれた食事性のルテインは、体内の主にどのような器官や組織にどの程度の濃度で存在が認められるのでしょうか。

Khachikら(HPLC‐MS分析)[10,13]、Hataら(ラマン分光法、HPLC分析)[14]の研究グループは、これまでにヒトの肝臓[13]、肺[13]、乳房[13]、子宮頚部[13]、皮膚[14]、大腸[10]、前立腺[10]といった組織から1 gあたりngからμgのレベルでカロテノイドとそれらの代謝物について過去に類をみない包括的な検出を行い、ヒトの血清中に存在が認められる食事性カロテノイドがこれらの器官や組織にも蓄積してることを明らかにしました(表2)。

| 表2. | ヒトの組織と皮膚における食事性カロテノイドとそれらの代謝物 |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

長年にわたってKhachikらは、さまざまな食事療法を受けたヒトの血清について広範囲の分析を行い、血清カロテノイドの相対濃度は食品に含まれるカロテノイドの比を(少なくともある程度まで)反映していることを明らかにしています。したがって、組織中に認められる一定のカロテノイドの特異的に高い濃度は、その組織による血清からの選択的なカロテノイドの取り込みに起因している可能性があるかもしれません[11]。

眼の組織におけるルテインの分布:

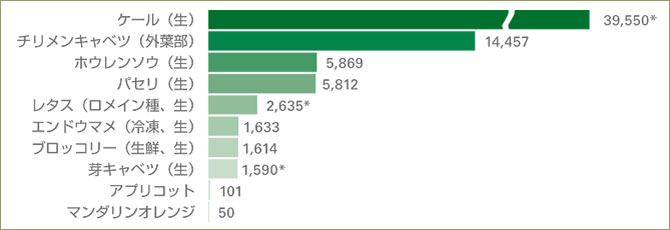

1945年、ハーバード大学のWald教授によってヒト網膜の黄斑部(図4)に黄色の色素の存在が認められました。

- 図4.

- 眼組織の断面模式図

「黄斑色素」と呼ばれるその色素は酸素分子を含んだカロテノイドあるいはキサントフィルで、おそらくルテインないしは緑葉自体に含まれるキサントフィルであることが分かり、哺乳類の網膜でこの種のカロテノイドの存在が初めて確認されました[15]。

Waldの発見から40年後、Boneらが行った研究から、ヒトの黄斑色素はクロマトグラフ法によって分離可能な2種類の成分、(3R,3'R,6'R)-β,ε-carotene-3,3'-diolと(3R,3'R)-β,β-carotene-3,3'-diolから構成されていることが明らかになりました。これらの成分は、それぞれルテイン、ゼアキサンチンとして同定されました[16]。

1997年、Khachikらは、ヒトとアカゲザル(Macaca mulatta)の網膜からカロテノイドとそれらの代謝物を合わせた14種類を完全に特徴付けし、ルテインとゼアキサンチンの酸化代謝物の存在を証明しました[17]。

ヒト網膜におけるカロテノイドの代謝変換の過程で鍵となるルテインと3'-epilutein(ルテイン・ゼアキサンチンの代謝物)の直接的な酸化生成物である3-hydroxy-β,ε-caroten-3'-oneの存在から、ルテインやゼアキサンチンが黄斑部を短波長の可視光線(青色光)から保護するために抗酸化剤としての機能を果している可能性のあることが結果から示唆されました。

2000年代に入ると、眼の生理学についてより優れた洞察を得るために、ユタ大学Moran Eye CenterのBernsteinらの研究グループがメリーランド大学のKhachikらの研究グループと共同でヒトのすべての眼組織における食事性のカロテノイドとそれらの酸化代謝物の全種類について同定、定量化を行いました[18]。

ここでは、眼の主要組織におけるルテイン、ゼアキサンチンとそれらの代謝物の定量的データを表3に示します(なお、個々の眼組織におけるルテインとゼアキサンチンの含有レベルに関するデータの詳細につきましてはゼアキサンチンのページをご参照ください)。

| 表3. | ヒト眼組織の抽出物における食事性ルテイン、ゼアキサンチンとそれらの代謝物の含有レベル |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

これらの研究結果から、眼の組織に存在するルテイン、ゼアキサンチン、及び他のカロテノイドが、光によって誘発される酸化的損傷と老化から眼を保護するために果している重要な役割がさらに裏付けられました。

報告されているルテインの健康上の利点

これまでに科学雑誌や学術会議で発表された研究から、ルテインは生体内における特徴的な分布を少なくとも部分的に反映しながら、とりわけ以下のような分野でそれぞれ他の異なる種類の栄養成分と共に重要な役割を担っている可能性のあることが報告されています。

抗酸化活性

ルテインは他の主要なカロテノイドと共に、以下に述べる多くの健康問題の原因となる活性酸素種(なかでも一重項酸素)やフリーラジカルを消去あるいは捕捉するのに有効であるとされています。

さらに、有効性は単独よりカロテノイド混合物としてのほうが高く、その相乗効果はルテインあるいはリコピンが共存する場合に最も顕著となるという報告も見受けられます[19]。

また、ルテイン、ゼアキサンチンといった限られた種類のカロテノイドとそれらの代謝物が局在する水晶体や網膜中心部では[16,20]、ルテインとゼアキサンチンの2種類のカロテノイドがそのような組織で生じる酸化的ストレスに対して抑制作用を及ぼしている可能性のあることが多くの研究で示唆されています[17,21-26]。

心血管系疾患

トゥールーズ(南仏)の住民はベルファスト(北アイルランド)の住民に比べて冠状動脈性心疾患の発生率が非常に低いことから、英国の研究グループはこれら二種類の人口集団における抗酸化ビタミンとカロテノイドの血漿中濃度の比較を行いました。

その結果、トゥールーズの男女でキサントフィル濃度が2倍高く、なかでもルテインとβ-クリプトキサンチンが顕著であったため、今後の冠状動脈性心疾患予防に関する調査ではキサントフィルカロテノイドが主要候補となることが過去の報告で予測されました[28]。

疫学調査を含むこれまでの研究で[27-31]、ルテインをはじめとするカロテノイドのような抗酸化性物質の血中濃度、あるいはそれらを豊富に含む食品の消費と心血管系のリスクの間に逆の関係が見出され、カロテノイドは酸化ストレスとの関係が指摘されている心血管系の疾患の発生機序に重要な役割を果たしている可能性が示唆されています。

加齢性眼疾患(加齢黄斑変性、白内障)

ライフスタイルの欧米化と社会の高齢化に伴って生じる健康問題は私たちの視機能にも及び、白内障に加え、これまで西洋社会における失明の主要な原因とされてきた加齢黄斑変性(AMDとも呼ばれ、視覚をつかさどる網膜の中心領域が障害されて起る非可逆性の疾患とされています。関連情報はゼアキサンチンのページでもご覧いただけます)のリスクが日本においても今後高齢者を中心に拡大する恐れがあります[32]。

ヒトの水晶体と網膜中心部に特異的に集積する黄色の色素(黄斑色素)は主にルテインとゼアキサンチンの2種類のキサントフィルカロテノイドから構成されていることが明らかにされ[13,15]、これらの食事性カロテノイドは、提案されている二つの機能(光学的フィルター、抗酸化剤)により、そのような眼組織が障害されて生じる健康問題のリスク低減に極めて重要な役割を担っている可能性のあることが多数の研究結果から示唆されています[33-58]。

皮膚の健康と栄養

私たちの皮膚は人体における最大の器官というだけでなく、外部環境との接点として、また外界から受けるさまざまな刺激に対する第一線の防衛として働いており、皮膚の担っている役割は決して少なくありません。

身体部位ごとに皮膚における濃度が異なるカロテノイドのうちの一つであるルテインは、経口補給あるいは局所塗布によって皮膚脂質過酸化、皮膚水和、皮膚弾性、光防護活性のようなパラメータを改善することがヒトと実験動物の両方で明らかにされ、ルテインあるいはルテインと他の抗酸化栄養素の組み合わせのもたらす防護作用が光老化や光発癌の抑制につながるかさらに検討が続けられています[59-70]。

ある種の癌

今日まで行われてきた多数の疫学調査から、カロテノイドを豊富に含む野菜・果物の充分な消費が種々のタイプの癌のリスク低下に関連していることが明らかにされています[71]。

癌に対するカロテノイドの防護効果について提案されている作用機構はそれらのカロテノイドが有する抗酸化能に基づいているとする1995年の報告では、カロテノイドのなかでもとりわけヒトの血清同様食品中にも豊富に見出されるルテインとリコピンが強い抗酸化力を有している可能性があると考えられ、β-カロテン以外にこのようなカロテノイドについても化学予防因子としての潜在的な可能性をさらに調査する必要性のあることが述べられています[72]。

それ故、カロテノイド豊富な野菜・果物の高摂取を一定の癌の発生リスク低下と関連付けた疫学調査を解釈する場合、この保護作用がβ-カロテンのみに起因していると考えるべきではなく、あらゆる食事性カロテノイド、とりわけ血中に見出されるカロテノイドの複合的な作用をより良く理解することが重要であるとされています。そのためKhachikらは、1997年に発表した論文の中で、将来ヒトを対象にして行われる臨床試験には表1に示したものと同じ比率のカロテノイド混合物を用いることを提案しています[9]。

- 最近の研究から

- 文献データベース

- ルテインあるいはルテインと他の栄養成分との組み合わせが果たす役割は、上述の分野以外でも解明が進んでいます。関連情報は、疫学調査、臨床試験、あるいは in vitro、in vivo 実験の結果から得られた興味深い所見とともに、最近の研究から、文献データベースのページで随時取り上げてまいります。折に触れてご確認いただけましたら幸いです。

参考文献・参考URL

- 1.

-

- http://georges.dolisi.free.fr/index.htm (accessed March 2009)

- 2.

-

- Holden JM, Eldridge AL, Beecher GR, Buzzard IM, Bhagwat S, Davis CS, Douglass LW, Gebhardt S, Haytowitz D, Schakel S. Carotenoid content of U.S. foods: an update of the database. J Food Compost Anal. 1999;12:169-96.

- 3.

-

- Hart DJ, Scott KJ. Development and evaluation of an HPLC method for the analysis of carotenoids in foods, and the measurement of the carotenoid content of vegetables and fruits commonly consumed in the UK. Food Chem. 1995;54:101-111.

- 4.

-

- Sommerburg O, Keunen JF, Bird AC, van Kuijk FJ. Fruits and vegetables that are sources for lutein and zeaxanthin: the macular pigment in human eyes. Br J Ophthalmol. 1998 Aug;82(8):907-10.

- 5.

-

- Goodrow EF, Wilson TA, Houde SC, Vishwanathan R, Scollin PA, Handelman G, Nicolosi RJ. Consumption of one egg per day increases serum lutein and zeaxanthin concentrations in older adults without altering serum lipid and lipoprotein cholesterol concentrations. J Nutr. 2006 Oct;136(10):2519-24.

- 6.

-

- Wenzel AJ, Gerweck C, Barbato D, Nicolosi RJ, Handelman GJ, Curran-Celentano J. A 12-wk egg intervention increases serum zeaxanthin and macular pigment optical density in women. J Nutr. 2006 Oct;136(10):2568-73.

- 7.

-

- Khachik F. Distribution and metabolism of dietary carotenoids in humans as a criterion for development of nutritional supplements. Pure Appl Chem. 2006; 78(8): 1551-7.

- 8.

-

- Khachik F. Process for isolation, purification, and crystallization of lutein from saponified marigolds oleoresin and uses thereof. US Patent 5,382,714, Jan. 17, 1995.

- 9.

-

- Khachik F, Nir Z, Ausich RL, Steck A, Pfander H. Distribution of carotenoids in fruits and vegetables as a criterion for the selection of appropriate chemopreventive agents. In: Yoshikawa T, Ohigashi H, eds. Food Factors for Cancer Prevention. Tokyo: Springer-Verlag; 1997. 204-8.

- 10.

-

- Khachik F, Carvalho L, Bernstein PS, Muir GJ, Zhao DY, Katz NB. Chemistry, distribution, and metabolism of tomato carotenoids and their impact on human health. Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 2002 Nov;227(10):845-51.

- 11.

-

- Khachik F, Spangler CJ, Smith JC Jr, Canfield LM, Steck A, Pfander H. Identification, quantification, and relative concentrations of carotenoids and their metabolites in human milk and serum. Anal Chem. 1997 May 15;69(10):1873-81.

- 12.

-

- Jackson JG, Zimmer JP. Lutein and zeaxanthin in human milk independently and significantly differ among women from Japan, Mexico, and the United Kingdom. Nutr Res. 2007 Aug; 27(8):449-53.

- 13.

-

- Khachik F, Askin FB, Lai K. Distribution, bioavailability, and metabolism of carotenoids in humans. In: Bidlack WR, Omaye ST, Meskin MS, Jahner D. Eds. Phytochemicals, a New Paradigm. Lancaster, PA: Technomic Publishing; 1998. 77-96.

- 14.

-

- Hata TR, Scholz TA, Ermakov IV, McClane RW, Khachik F, Gellermann W, Pershing LK. Non-invasive Raman spectroscopic detection of carotenoids in human skin. J Invest Dermatol. 2000;115:441-8.

- 15.

-

- Wald G. Human vision and the spectrum. Science. 1945 Jun; 101(2635):653-658.

- 16.

-

- Bone RA, Landrum JT, Tarsis SL. Preliminary identification of the human macular pigment. Vision Res. 1985;25(11):1531-5.

- 17.

-

- Khachik F, Bernstein PS, Garland DL. Identification of lutein and zeaxanthin oxidation products in human and monkey retinas. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1997 Aug;38(9):1802-11.

- 18.

-

- Bernstein PS, Khachik F, Carvalho LS, Muir GJ, Zhao DY, Katz NB. Identification and quantitation of carotenoids and their metabolites in the tissues of the human eye. Exp Eye Res. 2001 Mar;72(3):215-23.

- 19.

-

- Stahl W, Junghans A, de Boer B, Driomina ES, Briviba K, Sies H. Carotenoid mixtures protect multilamellar liposomes against oxidative damage: synergistic effects of lycopene and lutein. FEBS Lett. 1998 May 8;427(2):305-8.

- 20.

-

- Yeum KJ, Taylor A, Tang G, Russell RM. Measurement of carotenoids, retinoids, and tocopherols in human lenses. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1995 Dec;36(13):2756-61.

- 21.

-

- Khachik F, Beecher GR, Smith JC. Lutein, lycopene, and their oxidative metabolites in chemoprevention of cancer. J Cell Biochem. 1995;22 Suppl:236-46.

- 22.

-

- Rapp LM, Maple SS, Choi JH. Lutein and zeaxanthin concentrations in rod outer segment membranes from perifoveal and peripheral human retina. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000 Apr;41(5):1200-9.

- 23.

-

- Thomson LR, Toyoda Y, Langner A, Delori FC, Garnett KM, Craft N, Nichols CR, Cheng KM, Dorey CK. Elevated retinal zeaxanthin and prevention of light-induced photoreceptor cell death in quail. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002 Nov;43(11):3538-49.

- 24.

-

- Thomson LR, Toyoda Y, Delori FC, Garnett KM, Wong ZY, Nichols CR, Cheng KM, Craft NE, Dorey CK. Long term dietary supplementation with zeaxanthin reduces photoreceptor death in light-damaged Japanese quail. Exp Eye Res. 2002 Nov;75(5):529-42.

- 25.

-

- Barker FM, Neuringer M, Johnson EJ, Schalch W, Koepcke W, Snodderly DM. Dietary zeaxanthin or lutein improves foveal photo-protection from blue light in xanthophyll-free monkeys. ARVO 2005 Annual Meeting. Fort Lauderdale, Florida, May 1-5, 2005.

- 26.

-

- Neuringer M, Johnson EJ, Leung IYF, Sandstrom MM, Barker FM, Schalch W, Snodderly DM. Macular pigment in monkeys: dietary effects on retinal biochemistry, morphology, susceptibility to light damage and macular aging. Abstract presented at the 14th International Symposium on Carotenoids. Edinburgh, UK, 17th - 22nd July 2005.

- 27.

-

- Howard AN, Williams NR, Palmer CR, Cambou JP, Evans AE, Foote JW, Marques-Vidal P, McCrum EE, Ruidavets JB, Nigdikar SV, Rajput-Williams J, Thurnham DI. Do hydroxy-carotenoids prevent coronary heart disease? A comparison between Belfast and Toulouse. Int J Vitam Nutr Res. 1996;66(2):113-8.

- 28.

-

- Morris DL, Kritchevsky SB, Davis CE. Serum carotenoids and coronary heart disease. The Lipid Reseearch Clinics Coronary Primary Prevention Trial and Follow-up Study. JAMA. 1994 Nov;272(18):1439-41.

- 29.

-

- Lidebjer C, Leanderson P, Ernerudh J, Jonasson L. Low plasma levels of oxygenated carotenoids in patients with coronary artery disease. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2007 Jul;17(6):448-56.

- 30.

-

- Park SK, Tucker KL, O'Neill MS, Sparrow D, Vokonas PS, Hu H, Schwartz J. Fruit, vegetable, and fish consumption and heart rate variability: the VA Normative Aging Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009 Jan 21.

- 31.

-

- Hozawa A, Jacobs DR Jr, Steffes MW, Gross MD, Steffen LM, Lee DH. Circulating carotenoid concentrations and incident hypertension: the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study. J Hypertens. 2009 Feb;27(2):237-242.

- 32.

-

- Yasuda M. Epidemiology of AMD. In: Shiraga F, Maeda N, eds. Ophthalmic Instruction Course No.5. Tokyo: Medical View; 2005 Nov:16-9.

- 33.

-

- Hammond BR Jr, Wooten BR, Snodderly DM. Density of the human crystalline lens is related to the macular pigment carotenoids, lutein and zeaxanthin. Optom Vis Sci. 1997 Jul;74(7):499-504.

- 34.

-

- Lyle BJ, Mares-Perlman JA, Klein BE, Klein R, Greger JL. Antioxidant intake and risk of incident age-related nuclear cataracts in the Beaver Dam Eye Study. Am J Epidemiol. 1999 May 1;149:801-9.

- 35.

-

- Chasan-Taber L, Willett WC, Seddon JM, Stampfer MJ, Rosner B, Colditz GA, Speizer FE, Hankinson SE. A prospective study of carotenoid and vitamin A intakes and risk of cataract extraction in US women. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999 Oct;70(4):509-16.

- 36.

-

- Brown L, Rimm EB, Seddon JM, Giovannucci EL, Chasan-Taber L, Spiegelman D, Willett WC, Hankinson SE. A prospective study of carotenoid intake and risk of cataract extraction in US men. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999 Oct;70(4):517-24.

- 37.

-

- Gale CR, Hall NF, Phillips DIW, Martyn CN. Plasma antioxidant vitamins and carotenoids and age-related cataract. Ophthalmology. 2001 Nov;108(11):1992-8.

- 38.

-

- Olmedilla B, Granado F, Blanco I, Vaquero M. Lutein, but not alpha-tocopherol, supplementation improves visual function in patients with age-related cataracts: a 2-y double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study. Nutrition. 2003 Jan;19(1):21-4.

- 39.

-

- Vu HT, Robman L, Hodge A, McCarty CA, Taylor HR. Lutein and zeaxanthin and the risk of cataract: the Melbourne visual impairment project. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006 Sep;47(9):3783-6.

- 40.

-

- Rodríguez-Rodríguez E, Ortega RM, López-Sobaler AM, Aparicio A, Bermejo LM, Marín-Arias LI. The relationship between antioxidant nutrient intake and cataracts in older people. Int J Vitam Nutr Res. 2006 Nov;76(6):359-66.

- 41.

-

- Christen WG, Liu S, Glynn RJ, Gaziano JM, Buring JE. Dietary carotenoids, vitamins C and E, and risk of cataract in women: a prospective study. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008 Jan;126(1):102-9.

- 42.

-

- Moeller SM, Voland R, Tinker L, Blodi BA, Klein ML, Gehrs KM, Johnson EJ, Snodderly DM, Wallace RB, Chappell RJ, Parekh N, Ritenbaugh C, Mares JA; CAREDS Study Group; Women's Helath Initiative. Associations between age-related nuclear cataract and lutein and zeaxanthin in the diet and serum in the Carotenoids in the Age-Related Eye Disease Study, an Ancillary Study of the Women's Health Initiative. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008 Mar;126(3):354-64.

- 43.

-

- Dherani MK, Murthy GV, Gupta SK, Young I, Maraini G, Camparini M, Price GM, John N, Chakravarthy U, Fletcher A. Blood levels of vitamin C, carotenoids and retinol are inversely associated with cataract in a north Indian population. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008 Apr 17.

- 44.

-

- Seddon JM, Ajani UA, Sperduto RD, Hiller R, Blair N, Burton TC, Farber MD, Gragoudas ES, Haller J, Miller DT, Yannuzzi LA, Willett W. Dietary carotenoids, vitamin A, C, and E, and advanced age-related macular degeneration. JAMA. 1994;272:1413-20.

- 45.

-

- Bone RA, Landrum JT, Dixon Z, Chen Y, Llerena CM. Lutein and zeaxanthin in the eyes, serum and diet of human subjects. Exp Eye Res. 2000 Sep;71(3):239-45.

- 46.

-

- Bone RA, Landrum JT, Mayne ST, Gomez CM, Tibor SE, Twaroska EE. Macular pigment in donor eyes with and without AMD: a case-control study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001 Jan;42(1):235-40.

- 47.

-

- Beatty S, Murray IJ, Henson DB, Carden D, Koh H, Boulton ME. Macular pigment and risk for age-related macular degeneration in subjects from a Northern European population. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001 Feb;42(2):439-46.

- 48.

-

- Mares-Perlman JA, Fisher AI, Klein R, Palta M, Block G, Millen AE, Wright JD. Lutein and zeaxanthin in the diet and serum and their relation to age-related maculopathy in the third national heatlh and nutrition examination survey. Am J Epidemiol. 2001 Mar 1;153(5):424-32.

- 49.

-

- Snellen EL, Verbeek AL, van den Hoogen GW, Cruysberg JR, Hoyng CB. Neovascular age-related macular degeneration and its relationship to antioxidant intake. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2002 Aug;80(4):368-71.

- 50.

-

- Bernstein PS, Zhao DY, Wintch SW, Ermakov IV, McClane RW, Gellermann W. Resonance Raman measurement of macular carotenoids in normal subjects and in age-related macular degeneration patients. Ophthalmology. 2002 Oct;109(10):1780-7.

- 51.

-

- Richer S, Stiles W, Statkute L, Pulido J, Frankowski J, Rudy D, Pei K, Tsipursky M, Nyland J. Double-masked, placebo-controlled, randomized trial of lutein and antioxidant supplementation in the intervention of atrophic age-related macular degeneration: the Veterans LAST study (Lutein Antioxidant Supplementation Trial). Optometry. 2004 Apr;75(4):216-30.

- 52.

-

- Koh HH, Murray IJ, Nolan D, Carden D, Feather J, Beatty S. Plasma and macular responses to lutein supplement in subjects with and without age-related maculopathy: a pilot study. Exp Eye Res. 2004 Jul;79(1):21-7.

- 53.

-

- Moeller SM, Parekh N, Tinker L, Ritenbaugh C, Blodi B, Wallace RB, Mares JA; CAREDS Research Study Group. Associations between intermediate age-related macular degeneration and lutein and zeaxanthin in the Carotenoids in Age-related Eye Disease Study (CAREDS): ancillary study of the Women's Health Initiative. Arch Ophthalmol. 2006 Aug;124(8):1151-62.

- 54.

-

- Nolan JM, Stack J, O'Donovan O, Loane E, Beatty S. Risk factors for age-related maculopathy are associated with a relative risk of macular pigment. Exp Eye Res. 2007 Jan;84(1):61-74.

- 55.

-

- Richer S, Devenport J, Lang JC. LAST II: Differential temporal responses of macular pigment optical density in patients with atrophic age-related macular degeneration to dietary supplementation with xanthophylls. Optometry. 2007 May;78(5):213-9.

- 56.

-

- SanGiovanni JP, Chew EY, Clemons TE, Ferris FL 3rd, Gensler G, Lindblad AS, Milton RC, Seddon JM, Sperduto RD. The relationship of dietary carotenoid and vitamin A, E, and C intake with age-related macular degeneration in a case-control study: AREDS Report No. 22. Arch Ophthalmol. 2007 Sep;125(9):1225-32.

- 57.

-

- Obana A, Hiramitsu T, Gohto Y, Ohira A, Mizuno S, Hirano T, Bernstein PS, Fujii H, Iseki K, Tanito M, Hotta Y. Macular carotenoid levels of normal subjects and age-related maculopathy patients in a Japanese population. Ophthalmology. 2008 Jan;115(1):147-57.

- 58.

-

- Tan JS, Wang JJ, Flood V, Rochtchina E, Smith W, Mitchell P. Dietary Antioxidants and the Long-term Incidence of Age-Related Macular Degeneration The Blue Mountains Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 2008 Feb;115(2):334-41.

- 59.

-

- Greenway HT, Pratt S, Craft N. Skin tissue levels of carotenoids, vitamin A, and antioxidants in photodamaged skin. Mohs Surgery Unit, Division of Dermatology and Cutaneous Surgery, Scripps Clinic, La Jolla, CA, 1999.

- 60.

-

- Faulhaber D, Ding W, Granstein RD. Lutein inhibits UVB radiation-induced tissue swelling and suppression of the induction of contact hypersensitivity (CHS) in the mouse (Abstract). The Society of Investigative Dermatology, 62nd Annual Meeting, Washington D.C., 2001, p. 497.

- 61.

-

- Morganti P, Bruno C, Guamen F, Cardillo A, Del Ciotto P, Valenzano F. Role of topical and nutritional supplement to modify the oxidative stress. Intl J Cosmet Sci. 2002 Dec;24(6):331-9.

- 62.

-

- Heinrich U, Gärtner C, Wiebusch M, Eichler O, Sies H, Tronnier H, Stahl W. Supplementation with beta-carotene or a similar amount of mixed carotenoids protects humans from UV-induced erythema. J Nutr. 2003 Jan;133(1):98-101.

- 63.

-

- González S, Astner S, An W, Goukassian D, Pathak MA. Dietary lutein/zeaxanthin decreases ultraviolet B-induced epidermal hyperproliferation and acute inflammation in hairless mice. J Invest Dermatol. 2003 Aug;121(2):399-405.

- 64.

-

- Lee EH, Faulhaber D, Hanson KM, Ding W, Peters S, Kodali S, Granstein RD. Dietary lutein reduces ultraviolet radiation-induced inflammation and immunosuppression. J Invest Dermatol. 2004 Feb;122(2):510-7.

- 65.

-

- Dorgan JF, Boakye NA, Fears TR, Schleicher RL, Helsel W, Anderson C, Robinson J, Guin JD, Lessin S, Ratnasinghe LD, Tangrea JA. Serum carotenoids and alpha-tocopherol and risk of nonmelanoma skin cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2004 Aug;13(8):1276-82.

- 66.

-

- Morganti P, Fabrizi G, Bruno C. Protective effects of oral antioxidants on skin and eye function. Skinmed. 2004 Nov-Dec;3(6):310-6.

- 67.

-

- Heinrich U, Tronnier H, Stahl W, Béjot M, Maurette JM. Antioxidant supplements improve parameters related to skin structure in humans. Skin Pharmacol Physiol. 2006;19(4):224-31.

- 68.

-

- Palombo P, Fabrizi G, Ruocco V, Ruocco E, Fluhr J, Roberts R, Morganti P. Beneficial long-term effects of combined oral/topical antioxidant treatment with the carotenoids lutein and zeaxanthin on human skin: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Skin Pharmacol Physiol. 2007;20(4):199-210.

- 69.

-

- Astner S, Wu A, Chen J, Philips N, Rius-Diaz F, Parrado C, Mihm MC, Goukassian DA, Pathak MA, González S. Dietary lutein/zeaxanthin partially reduces photoaging and photocarcinogenesis in chronically UVB-irradiated Skh-1 hairless mice. Skin Pharmacol Physiol. 2007 Aug 24;20(6):283-291.

- 70.

-

- Heinen MM, Hughes MC, Ibiebele TI, Marks GC, Green AC, van der Pols JC. Intake of antioxidant nutrients and the risk of skin cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2007 Dec;43(18):2707-16.

- 71.

-

- van Poppel G. Carotenoids and cancer: an update with emphasis on human intervention studies. Eur J Cancer. 1993;29A(9):1335-44.

- 72.

-

- Khachik F, Beecher GR, Smith JC. Lutein, lycopene, and their oxidative metabolites in chemoprevention of cancer. J Cell Biochem. 1995;22 Suppl:236-46.